The force awakens along the wild Atlantic Way

A long long time ago…

Pursued and persecuted by the empire, a small band of surviving warrior monks finds refuge on a rocky outpost on the very edge of the galaxy. There, in solitary isolation, they train and pray awaiting the day when the Empire will fall and balance is restored to the force.

Thus begins the story about that time I flew the Millenium Falcon to the first Jedi temple… well sort of.

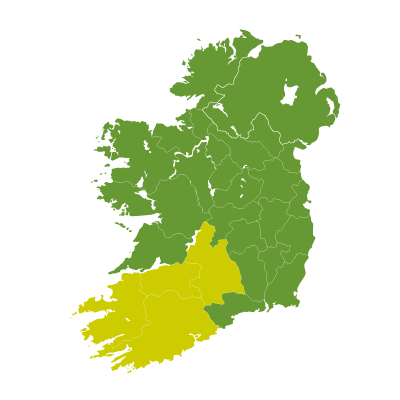

A part of me suspects that it was no coincidence that the latest installments of the StarWars saga would use the 8th Century monastery of Skellig Michael off the coast of Co.Kerry on Ireland’s wild atlantic way as a backdrop. There is a certain synchronicity (to use a Jungian expression) to events in Ireland one comes to learn with time.

It had long been rumoured that the small monastic settlement perched 700 odd feet atop the towering rock would be the refuge of Luke Skywalker in the movie.

These enigmatic rocks, immortalized in a phrase by Shaw “I tell you the thing does not belong to any world that you and I have lived and worked in: it is part of our dream world”. oft quoted by guides such as myself, the paragraph taken from a letter penned by the playwright while staying in Sneem on the ring of Kerry in September of 1910 goes on to vividly describe the experience of western boat-people since time immemorial.

“Then back in the dark, without compass, and the moon invisible in the mist, 49 strokes to the minute striking patines of white fire from the Atlantic, spurting across threatening currents, and furious tideraces, pursued by terrors, ghosts from Michael, possibilities of the sea rising making every fresh breeze a fresh fright, impossibilities of being quite sure whither we were heading, two hours and a half before us at best, all the rowers wildly imaginative, superstitious, excitable, and apparently super-human in energy and endurance, two women sitting with the impenetrable dignity and quiet comeliness of Italian saints and Irish peasant women silent in their shawls with their hands on the quietest part of the oars (next to the gunwale) like spirit rappers, keeping the pride of the men at the utmost tension, so that every interval of dogged exhaustion and drooping into sleep (the stroke never slackening, though) would be broken by an explosion of “up-up-upkeep her up!” “Up Kerry!”; and the captain of the stroke oar — a stranger imported by ourselves, and possessed by ten devils each with a formidable second wind, would respond with a spurt in which he would, with short yelps of “Double it — double it — double it” almost succeed in doubling it, and send the boat charging through the swell”.

These enigmatic, majestic rocks. Some of the oldest geological land-forms in Europe, laid down between 360 and 374 million years ago during the Devonian period. Known as the age of fish, this was when our early ancestors waddled out of the ocean to check out the beaches of South county Kerry with a 99 (soft ice-cream) in hand. Presumed to be the first case of sunburn in Ireland, the footprints of this 300 million year old, four-legged Irish person are preserved to this day in a rock shelf on the the island of Valentia, within sight of the Skelligs on a good day.

Little is known of the rocks in the intervening period but by the 8th century A.D. at least we know that the larger of the rocks became home to a commnity of about a dozen eremetic Christian monks. These ascetic monks made the oft times treacherous 7 mile crossing from the mainland during the Celtic Christian golden age as it is known. there they lived in communion with the almighty at the very outer rim of this realm as close to the veil as one can come in this world. This wasn’t merely superstition on their part, this is as much the reality of the Skelligs today as ever it was, they are special, one of those liminal places you encounter every now and again if your lucky enough.

In open boats made from cow-hide stretched over a wooden frame they rowed back and forth to this threshold of the worlds.

Today similar craft called naomhóg or young saint in the english language, still ply these waters. Myth and legend say that the sons of Míl, Eremon and Ir, their sails filled with the dark wind of a magical storm were killed when their ship was wrecked on the island. The brothers were the first of the Gael to die in Ireland and their children are said to be our ancestors.

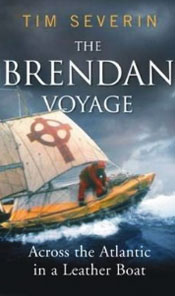

These stories were collated in the Lebor Gabála Éirenn or the book of the taking of Ireland in the later medieveal period. Medieval literature would also later attest that the same boat made the crossing of the wide Atlantic with Saint Brendan at the helm in the mid 6th century b.c. and it only took 7 years, wait… what!?!

A more modern documentary attests to Tim Severin and his brave crew having made the same crossing in the summer of 1976, the book the Brendan Voyage by Tim Severin is a modern classic at this stage and one of the best books I’ve ever read.

A more modern documentary attests to Tim Severin and his brave crew having made the same crossing in the summer of 1976, the book the Brendan Voyage by Tim Severin is a modern classic at this stage and one of the best books I’ve ever read.

Over the years I have had the privilege of visiting these enigmatic, majestic and for all their ancientness, almost ephemeral rocks.

Over a dozen times I’ve been to the Skelligs and each time I get to go I’m more excited than the last. The last time I was there it was in early November 2016. The first squalls of what would be Storm Angus were on the horizon and I was on tour with a family who has since become friends (a hazard of the job, meeting wonderful people).

The slow whine of the engine and whump, whump of the blades could be heard as we made our way out to the helipad. Beyond the tarmac extending south and west were the wood covered crags and hidden glens of the Beara peninsula. West of us stretched the Kenmare river broadening into the bay beyond the un-seasonally colorful little town. We took off from the Helipad of sheen falls resort.

George Lucas in writing the original StarWars was undoubtedly inspired by Irish as well as classical mythology. Maybe a return to Ireland was written in the stars – if you’ll excuse the pun.

For me the parallels between the central theme of the film and the historical reality are striking. The flight of the Jedi from the Emperor preserving their faith and training in hidden corners of the galaxy. The early desert fathers as they were known did the same, finding refuge in the Nitrian desert west of the Nile delta. The hermetic movement was massively influential in the forming of early Christianity, ‘turning the desert into a city’. Under the Roman Emperor Diocletian in the late 3rd century, persecution of Christians in the near east came to a head, further west the persecution was less severe and so began the hermetic movement to the farthest fringes of the known world seeking isolation and finding Communion with… The mighty Atlantic.

I’ve been to Skellig Michael a number of times over the years as a tour guide and feel honored to have had the opportunity, it really is a sacred place. A feeling of peace pervades the site, reluctant patience is required to negotiate each individual step. Slowly, mindfully ascending the near vertical flights it is impossible not to feel the raw power of the vast Atlantic, each step a tentative prayer from crashing waves hundreds of feet below.

Ironically for a place of peace the rock is dedicated to Saint Michael the warrior archangel who led an angel alliance against the fallen angel Lucifer in the war for heaven. Not so ironic given the weapons wielded by the monks, not unlike the Jedi in Lucas’ epic, are weapons of light and peace. Or to quote Yoda, ‘Remember, a Jedi’s strength flows from the force. Anger, fear, aggression, the dark side of the force are they. Easily they flow, quick to join you in a fight. If once you start down the dark path, forever will it dominate your destiny’

I sometimes wonder amidst the Starwars fever if something else hasn’t awoken in us. In the camping out of devoted fans outside cinemas worldwide, in the pilgrimage to desert film sets and now as Star Wars pilgrims flock to a holy rock in the southwest. Something powerful, ancient, something mysterious, something eternal.

Christmas in Dublin

A unique tailor-made Irish experience

Shanakee adventures recently had the uplifting experience of attending a concert in Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral. I brought a small-group of Scandinavian visitors to Dublin on a unique tailor-made Irish experience through the city’s Medieval and Viking past.

The venue was Christ Church Cathedral the oldest building in Dublin. The concert performed by the Adolf Frederik’s choir from Sweden is sponsored annually by IKEA and attended by the Swedish Ambassador to Ireland amongst other dignitaries. The event arranged by Dublin’s Swedish and Scandinavian communities, celebrates Santa Lucia the light bearer. Scandinavian ties in the one time Viking capital of Dublin go back over a thousand years and so this unique experience opens a window on to a fascinating story.

Outside the imposing walls of the Cathedral, the December evening in Ireland’s capital city was dry and frosty, a light breeze drove the chill air. Night had drawn in and the line along Christ Church’s railing lengthened. The smell of roasting malt barley infused the frosty westerly breeze. The aroma, carried from the mighty Guinness Storehouse only a few blocks upwind of us west along the river liffey is the essence of Dublin city centre and has been for over two hundred and fifty years.

While waiting in line my Scandinavian guests ask me about Christ Church and the Cathedral’s history.

“Well…” I begin,

“You needn’t go on, I think we understand” they reply

Encouraged and delighted by their cutting wit (two days in Dublin and they are already gone native) I continue…“If the turning of the first year brought us the story of Christ”

The turning of the first millennium brought us the story of Christmas as we know it today.

A lot has happened in the intervening years most of it lost to the mists of time but the folklore and stories that surround Christmas are powerful and resonate through the ages.

These stories were hard earned, carried through dark times they bare witness to thousands of generations past, thousands of lips, thousands of hearts, and thousands of chill nights praying for the first rays of morning.

In the year 795 a.d.

795 a.d. is a date we all learn as children at school, the first of the Pagan North men landed on our shores. Viking raiders aboard sleek hulled long-ships burned the Christian monastery on Rathlin island off the Giant’s Causeway coast in County Antrim.

Sea raiders from the fjords of Norway and the low countries of Denmark, we the Irish would mark them apart in our language as the Finn Gall or fair foreigner from Norway and the Dubh Gall or dark foreigner from Denmark. They would from that first raid spend the next two hundred years gouging lumps out of Ireland from bases in her river valleys. These bases would eventually become our major ports and cities, places like Vaderfjord (Weather fjord became Waterford) Inis Gall dubh (meaning Island of the Danes would become Limerick) and Corcagh (Meaning swamp, would become Cork city, well… you can’t have everything).

1000 A.D.

By the turn of the first millenium a.d. Dublin was a thriving port and a Viking capital to rival other cities like Yarvik (York) in England. The Finn Gall and the Dubh Gall by this stage had inter-married, forging necessary political alliances among powerful native clans. The children of these alliances were called the Gall Gael or the foreign Irish and the most famous of them was the son of the Norse king of York and Dublin and an Irish queen by the name of Gormflaith Ní Murchadh. Described in the icelandic sagas as the most beautiful of women, her son Sigtrygg Silkeskegg or Sitric Silkenbeard would be equally as beautiful. He was in fact(or as far as anyone can figure out in any case) grandson to Ivar the Boneless the son of Ragnar Lothbrok, a character made popular by the HBO series Vikings. Sitric would himself father a long line of underwear models to star in HBO series’ for years to come

Sitric was said to be the man who laid the foundation stone at Christ Church Cathedral on the high ground overlooking the Viking settlement at what is now wood quay in the year 1028 a.d.

Sitric was said to be the man who laid the foundation stone at Christ Church Cathedral on the high ground overlooking the Viking settlement at what is now wood quay in the year 1028 a.d.

The fierce north men

The Viking era had a profound and indelible influence on the course not just of Irish history but the history of Continental Europe, from the western steppes of Asia to the Atlantic rim to Sicily in the Mediterranean. Syracuse was attacked and Sicily conquered in 860 by Sitric’s grand uncle Björn Ironside (pictured right)

The Viking era had a profound and indelible influence on the course not just of Irish history but the history of Continental Europe, from the western steppes of Asia to the Atlantic rim to Sicily in the Mediterranean. Syracuse was attacked and Sicily conquered in 860 by Sitric’s grand uncle Björn Ironside (pictured right)

Along with international commerce, coinage and intensified trade the Vikings brought with them to Ireland their language, ideas and probably their most enduring legacy, their sagas and storytelling.

It wasn’t until well into the 12th Century that the last of the Pagan Viking kings would be baptized well over nine hundred years after the first Christian missions to Ireland, and so for almost 30 generations two distinct cultural traditions lived side by side.

The period of twelve days spanning the darkest days of midwinter was known to the old Norse as Jol or Jul (Christmas is still referred to as Jul pronounced Yule in the Scandinavian countries). This was the time when Odin, Father of the Gods or the JolFadr (Yule father: a guy with a long white beard flying through the sky basically) Father Christmas would lead the Gods on a hunt through the winter sky. Yule tide would eventually become Christmas tide as the two traditions were reconciled over time.

The period of twelve days spanning the darkest days of midwinter was known to the old Norse as Jol or Jul (Christmas is still referred to as Jul pronounced Yule in the Scandinavian countries). This was the time when Odin, Father of the Gods or the JolFadr (Yule father: a guy with a long white beard flying through the sky basically) Father Christmas would lead the Gods on a hunt through the winter sky. Yule tide would eventually become Christmas tide as the two traditions were reconciled over time.

For Shanakee and for many Scandinavians one of the most beautiful and enduring of the Vikings folk traditions is the marking of the long days and the long nights. The folk tradition of seasonal celebration is quite different here in Ireland where we enjoy mild southern latitudes when compared to the extremes of Scandinavia’s northern aspect, extending as it does all the way to the polar circle in the north. In Ireland with a farming tradition dating back over five thousand years and with milder winters and a longer growing season, we mark what are known as the cross quarter days (early spring and late Autumn) with festivals celebrating the sowing and the reaping.

In the far north of the world

In the far north celebrations mark the extremeties of the year, Midsummer marking summer’s height and Midwinter’s celebrations marking the longest night are observed. One of these old Viking folk traditions is Lussinatt or Lussifärd also known as Long Night which fell on the 13th of December under the old calendar system. The Lussi were seen as demons of the night. Some scholars believe that the name Lucifer derives from Lussifärd which translates as the Lussi’s passing over. It was thought far too dangerous to venture out on this the darkest of nights and so children and adults alike would stay indoors while the Lussi, trolls and dark elves emerged from the night and howled through the night sky above their homesteads. Fires would be lit in the hearth to deter the Lussi from descending through the smoke hole to snatch children and carry them off.

With the Viking conversion to Christianity and the intermarriage of ideas across the Viking world the story of the Lussi was destined to meet with that of Saint Lucy or Santa Lucia. When eventually they met one would inevitably become shadow to the other or to paraphrase Leonard Cohen through a crack shone the light.

With the Viking conversion to Christianity and the intermarriage of ideas across the Viking world the story of the Lussi was destined to meet with that of Saint Lucy or Santa Lucia. When eventually they met one would inevitably become shadow to the other or to paraphrase Leonard Cohen through a crack shone the light.

Saint Lucy

Saint Lucy was an early Christian martyr from the city of Syracuse in Sicily. Her story was already over four centuries old by the time Björn Ironside landed there with his fleet of longships in the 9th Century. Known as the light bearer Lucy brought light to terrified Christians hiding in darkness in the cities catacombs, Christians who were persecuted mercilessly under the Emperor Diocletian. Into the dark underworld Lucy carried food and water to the persecuted with a crown of light that she might free her hands to carry more food.

The entering of light into the underworld thus bringing life back to the earth and mankind after the longest night, is probably one of the most common and well attested of our earliest beliefs. It is the story that tells itself with every sunrise, with the ebbing of every tide and the passing of every winter.

The undying story of Christmas

Wishing you all a light filled and joyous festive season telling stories around the dinner table shared with friends and family.

“God Jul till er alla

Nollaig shona Díobh”

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to you all

Warmest blessings